This is how we say it in my language, which I just made up.

Language invention is the most thankless part of world-building. So naturally that’s where I started.

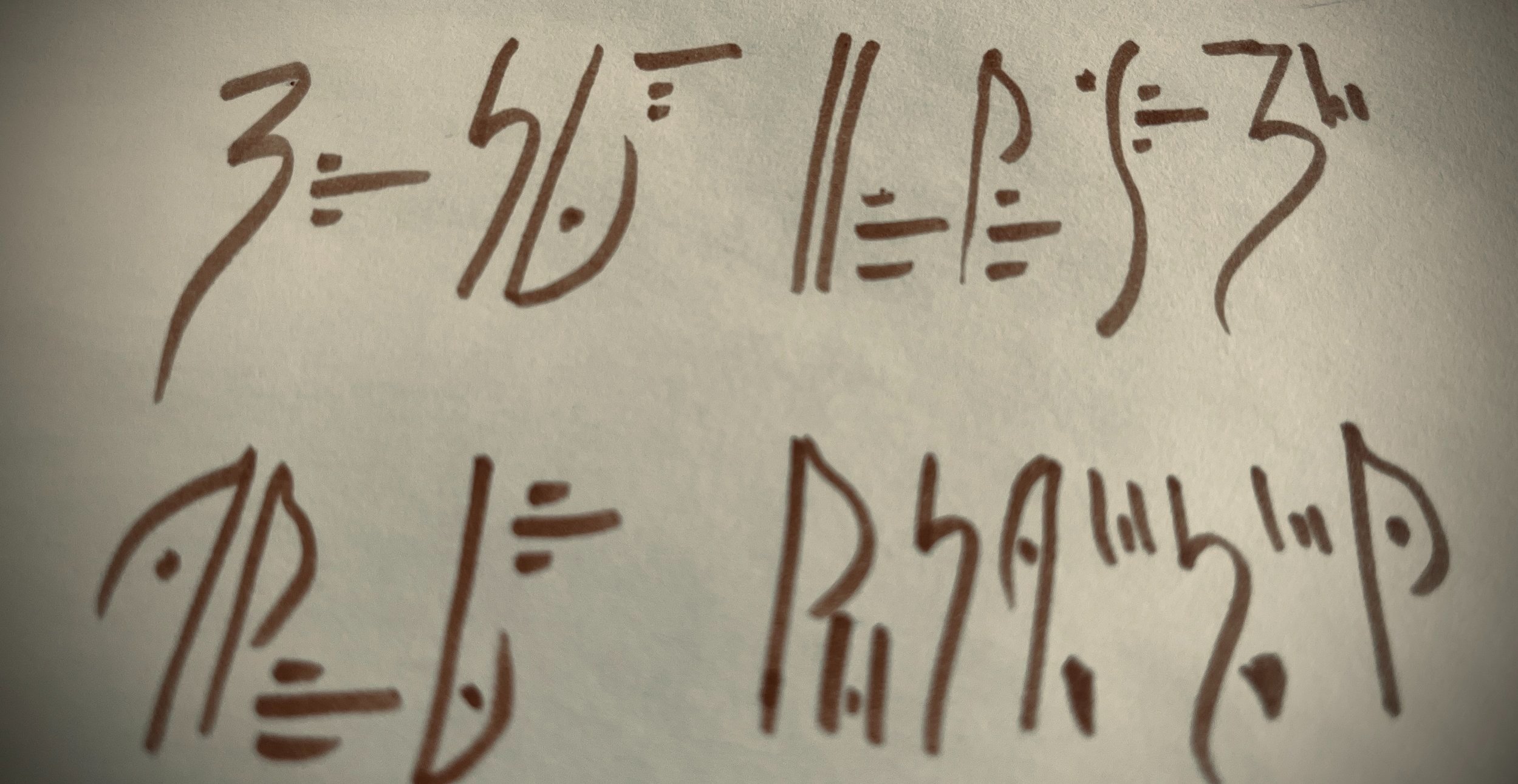

How to write, “Once upon a time, dragons ruled the earth” in Rumara. At least in theory. Can you find the typo?

Recently I decided to invent the language Rumara. It would be the language of the civilization along the banks of the Ruma, the World River, and one of the first and oldest languages. The name “Rumara” comes from “ruma,” or river, and “rara,” literally tongue, but also (as in English) speech or language.

That’s a lie, obviously. In fact, the word “rara” comes from the word “Rumara”, which I chose as the name of the language of Ruma because I thought it had a nice ring to it. It’s better than Rumish or Rumian, anyway. And the name Ruma is what I settled on for my river (and civilization) after months of tossing ideas around in my head. I just like the way it sounds. Luckily for me, “rara” is a great word for tongue - try saying it without using your tongue and you’ll see what I mean.

These vocabulary words from a game session a couple of decades ago formed the core of my language Rumara. I love that I have both the honorable and insulting words for the elders. FWIW, the word “jailbait” is super problematic.

This is the opposite of how languages develop in the real world. But this is for an imaginary language in a fantasy world for a D&D game that I may never play. It doesn’t need to evolve naturally, it just has to look like it did.

The world of Ruma is still in its brainstorming stages - there’s not even a map, just a rough draft and some scribbled notes (“The World Clock,” “House of Locks,” “City of Breach”). The river itself winds from the ice caps to the tropics, with space for a hundred kingdoms and a thousand adventures along its banks. I imagine great river giants towing ships upstream (for a price), a march of mushroom people huddled underneath parasols, a clockwork kingdom at odds with itself, a tyrannical kingdom built on a half-understood prophecy still whispered in an echoing tower…

So why start with language?

I like languages, I like the flavor they lend to a fantasy. And my brain is attracted to consistency, I want my place names to feel like part of something older, something historical. A language helps with that. So a few weeks ago I set down my goals for the language and got to work.

Rumara should sound interesting when translated. I am not going to force my players - presuming I have any - to learn a language. But I do want translations from my fantasy tongue to sound distinctive and consistent.

Rumara should be anchored in the metaphor of the river. The language should draw from currents and tides, paddles and sails - not horses and mountains.

The verbs have only a present tense. Long ago I introduced “Riverfolk” into a game of mine. For a dialect, I decided they only spoke in the present tense, which made their speech very distinctive in English. “Come with me, we see the elders. They speak to you of the raiders who burn the docks in the summer.” I like that philosophical, timeless mood - it suits a river people.

Tense and mood frame each phrase at the beginning. I imagine a language needs some kind of tense, though, so I decided to put it at the beginning of each sentence - very different from English! Partly I was being lazy - I studied Latin in high school, and I don’t really want to reinvent the pluperfect tense. Partly I was being poetic, in response to points 1 and 3, above. “It is written: the queen goes down to the valley, and meets the armies of her enemies.” I like the sound of that.

Any word can be either a noun, verb, or adjective. No word classes! This one is just neat, I love it. This goal is part intellectual challenge, part flavor, and part convenience - I only have to create 1/3 as many words! Also, screw adverbs, who needs them.

By this point I had decided on word order: Frame - Object - Subject - Verb. Apparently this is pretty rare in real languages, but I like the idea of putting the actor and act right next to each other. It could be an exasperating language, since if the speaker is cut off, you don’t know the point of the sentence!

So, a mix of thematic and tactical goals. I spent a lazy Sunday working up vocabulary and syntax, and ended up with a vocab list including some of the following:

brado: young man or woman (n); to bluster (v); headstrong, young (adj)

dimak: right hand (n); to take (in hand) (v); starboard (adj)

dinga: mushroom (n); to forage (v); some, a few (adj)

draka: dragon (n), to overwhelm (v); dragon-like (adj)

gundos: elder (respectful) (n); to survive, thrive (v); old, wise (adj)

lerai: sword (n); to stab, cut (v); sharp (long), incisive (adj)

rara: speech, language (n); to talk, tell (v); sentient, eloquent (adj)

safuun: season, year (n); to change, cycle (v); seasonal, years-old (adj)

And then I was ready to start writing really important sentences, like:

Azkan drakabo leraii

[(She) sworded the dragon]

Azkan: This is the frame, it means “in the past.” It always comes first in a phrase.

drakabo: This is the object of the sentence: draka (dragon) + bo, which identifies the direct object. I created two object suffixes: bo and mo, for people vs things, respectively. Why not? A smart narrator uses -bo for a dragon out of respect. Also, draka is pretty vanilla, but I firmly believe the word “dragon” should be recognizable in any language.

leraii: Verb form of sword - lerai - plus the verb ending -i. All verbs are present tense, but the endings tell the us who and how many.

This is where I got a little too clever. It occurred to me that a language with a rich storytelling background might use the first person to talk about the hero of the story, not just the speaker. So the ending -i could either mean, “I do it” or “the hero that we’re talking about does it.” I have not worked through the ramifications of this yet.

There is no “she” in the sentence - not unusual in languages with different verb forms like this. But that does mean that technically, the sentence by itself is leaving out some information. Let’s try that again.

Azkan drakabo idan leraiun

Idan gives us a third-person pronoun - dan - with a female gender marker tacked on. Now, I had already decided that pronouns in Rumara don’t express gender; and it would be considered rude and weird to put a gender marker in front of a pronoun about a fight. You might do it in a romance where you wanted to stress the various genders of the characters, or in a text about medicine where physical sex might be important. But normally you would leave it out.

Note that leraii - I (or the hero) swords - has become leraiun - a third party swords. This matches the pronoun, dan [verb]un. If if wanted to stay in the heroic narrative, it would be first person - yi leraii, or possibly iyi leraii if the narrator is really into gender.

Isn’t this fun? I was feeling pretty proud of myself after putting Rumara through its paces. So I brought this up with my buddy Greg, and he asked, “Could you write a sentence where dragon was the verb and sword was the object? Like:

“You would fight me, stripling of fifteen winters? Longer than that has it been since the day I first dragoned my sword!”

Greg’s a lawyer.

So I gave it a shot, and it took me two days. I had to create phrases for relative time, figure out subclauses, and come up with a numbering system. This is what I came up with:

A’koz yibo xio’nga zon-bek safuu’nga brado varaio’t?

Azkan yi’nga leraibo yi drakai. ‘Kee gundo’ngana h’st xiovatchi hinga ny obzun!

Literally this means something like:

Can it be that you propose: me, you 15-season youth, fights alone?

Once it was: my sword I dragon. I suggest: older than you that day appears to be!

Are you not entertained? Let’s take a look.

A’koz is a frame - A makes it a question, and ‘koz (short for rako) means somebody is proposing (rather than something is). In this case it means “is it true that you are proposing.” Azkan, the frame that opens the second sentence,, simply means past tense, and ‘kee means “I propose.” Honestly, the whole frame idea worked way better than I expected.

‘nga is the suffix for adjectives. So xio’nga zon-bek safuu’nga is a big adjective phrase that means “your 15-season/year…”, modifying brado, or youth/punk. Looking at it, this feels like it could mean either “your child” or “you (who are a child). Confusing, but so is English: “Let’s talk about your youth” could be about your son or your childhood. So I am ok with this.

varaio’t = vara (duel) + io (second-person verb ending for an enemy, not friend) + ‘t (only). I created a couple of suffixes to denote plural forms of verbs, and decided - why not have a marker specifically for only one thing? It is probably an insult in this case - the difference between “you’re going to fight me?” and “you’re going to fight me alone?”

Those stops - ‘ - are intended to be silent vowels, a glottal stop. Either a full syllable, or just a separator. So yi’nga sounds more like yi-in-ga. It’s a work in progress, I am trying to keep them from being needless ornamentation.

yi’nga leraibo yi drakai is really straightforward: [my] [sword, noun] [I] [dragon, 1st person verb]. The fun part is that -bo is used for people, not objects, so the speaker is talking about their sword like it’s a person.

Also what does this mean? Greg proposed that it means “I bloodied my sword”, only more bad-ass, since was against a dragon. Not what I had in mind for the word, but it does work.

gundo’ngana h’st xiovatchi means “older than you”: gundo for old, ‘ngana as the comparative adjective ending. Xio is “you, enemy”, and -vatchi is the ending for indirect objects, implying “from or than”. hinga ny means “that day”, and it’s the subject - so “that day is older than you.” Which… I think that works, even if it’s not at all how we would say it in English.

obzun is the third-person verb form of obza, and means “seems.” I decided that Rumara does not have a verb “to be” as such, and “seems” is the alternative. This is not a new idea, people have been talking about dropping the verb “to be” from English for a long time.

This may be a good time to mention that I speak only one language - English.

I studied Latin in high school and some French in college; I’ve also been studying Japanese on Duolingo. But I have not learned to speak any of them. That said, after failing to learn three languages, surely I can fail to learn a fourth.

I had help, though. In addition to cribbing liberally from Japanese (verbs at the end of sentences!) and Latin (verb endings!), I picked up a few books on language creation. I had not realized how many books there are on this topic, or what a rich community of of language constructors - conlangers - exists. Honestly, I still don’t - I have only just begun learning about language. But these books were very helpful.

The Art of Language Invention by David J. Peterson is the book that convinced me to actually sit down and write up my language. He is the guy who invented the languages in the Game of Thrones tv show - based on a few samples from Martin in the book.

This book is at once conversational and deep. It doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to the complexity of creating a language, and dives right into pronunciation and phonetics. At the same time, it doesn’t feel impossible. The book winds Peterson’s case studies throughout, comparing the different principles at work in Dothraki and, say, the various alien languages in the sci-fi show Defiance (mediocre show, fantastic world-building.)

This approach makes the entire process more… approachable. I learned a lot about how languages form an evolve from this book, and I found it an excellent starting point.

The second book I dug into is The Language Construction Kit by Mark Rosenfelder, who is a big name in the constructed language game. Just a glance at his website tells me is is about 1000% more serious about this stuff than 99% of fantasy writers and gamers.

This book is exactly what it says on the cover: a breakdown of all the facets of a language and how they inform each other. If you have an organized mind, this book will hit the spot. It is both more basic and more advanced that Peterson’s book - but you can open to any page and instantly learn something.

All in all, I am glad I read them in the order I did. Peterson’s autobiographical approach made the art of language building a little more personal and appealing, which primed me to want to know more. Rosenfelder scratched that itch.

Neither books wastes an inch of copy, either. I love a book written by a true enthusiast, a geek’s geek, and these both qualify. That said, they are the only books on language creation I have read so far, so take this with a grain of salt.

I would say “until next time” in Rumara, if I had a word for “until.” Or “next.” Or “time.”

I’m still pretty fascinated by this experience, so I’ll probably keep writing about it. I found myself thinking: why does English have comparative and superlative word endings, but not diminutive endings? Why do we have “sweeter, sweetest,” but not “sweetless, sweetleast?” And why have I never wondered about that before?

I am sure wondering about it now. And hopefully so are you.